Sharkman's World

To Save & Protect Sharks

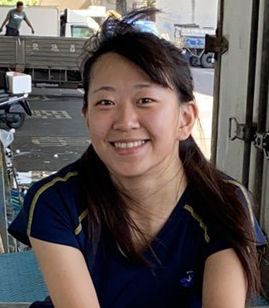

The Sharkman meets Chi-Ju Yu (Debbie)

Hello Debbie.

Welcome to

SHARKMAN’S WORLD

Sharkman: Can you please tell us a little about yourself?

Debbie: I’m Chi-Ju Yu (Debbie), a postdoc researcher from Dr. Shoou-Jeng Joung’s lab in National Taiwan Ocean University. Since last year, my postdoc project has been to use acoustic telemetry to track large elasmobranchs around Taiwan waters. This chance is supported by the Georgia aquarium. I have worked on sharks since I started my master degree 13 years ago. I mainly studied the fishery biology of sharks in the fish market, including feeding ecology, reproduction, and age and growth research. My master thesis was about the feeding ecology of three Carcharhinus species, and my PhD thesis was about the feeding and reproduction of the Megamouth shark (Megachasma pelagios). As a researcher, I aim to provide information for the sustainable management of shark resources in Taiwan.

Sharkman: When did sharks come into your life?

Debbie: I don't quite remember the exact first time, but I tried to recall my memory. My parents took me to Daxi fishmarket (in Yilan City) very often when I was little, it was likely the first time I saw some small shark species (maybe a Dogfish or something like that). However, the bright colorful fishes might have caught more of my attention at that moment.

Sharkman: At that moment.... but than it changed.

Debbie: Yes. Sharks are fascinating and enigmatic creatures, found across various water layers and habitats, yet they often present many unresolved mysteries. These mysteries may be related to their species' preferences, and sexual or life history stages, all of which make them truly captivating for me.

Sharkman: Do you remember your first underwater shark encounter?

Debbie: I cannot really remember it, but I think my first underwater shark encounter was with my lab members to release a bycatch Whale shark in the eastern waters of Taiwan about 10 years ago.

I didn't have any diving experience at that moment, therefore, I tried to get close to the sea surface for the Whale shark. I was touched by the beautiful White spots of the Whale shark and truly hope that we can solve the problems that we didn't know before.

Sharkman: Did you ever feel in danger during your dives?

Debbie: So far, all my experiences being in the water with cartilaginous fishes have been in very safe and controlled environments, such as tagging and releasing Bowmouth Guitarfish (Rhina ancylostoma), Whale shark (Rhincodon typus), and Megamouth shark, or diving in the aquarium. Therefore, I’ve never had an unexpected experience before, nor have I been with particularly curious species (EX: Tiger shark, Galeocerdo cuvier). I only felt in danger by diving with jellyfish.

Sharkman: I totally agree. Debbie, like myself, you share a great interest for the Megachasma pelagios (the Megamouth Shark). What attracted you to this species?

Debbie: My involvement in Megamouth shark research began by chance. Initially, I was just assisting our lab and government in dealing with the capture and report of some eye-catching elasmobranch species from fishers. At the start of my Ph.D., I intended to study the feeding ecology of various large shark species. Coincidentally, my advisor received approval for a project related to Whale sharks, therefore, I was strongly suggested to work on Whale sharks. At the time, I felt Whale shark research was dull because it's the filter-feeding shark species (not the top predator). However, after a while, one day, something suddenly came to my mind when I was sitting in the lab " Oh, the Megamouth shark is also a filter-feeding species". Since I was already spending time dealing with the samples and data, I thought I might as well explore if there was anything interesting about both the Megamouth and Whale sharks as filter feeders. Finally, I became deeply interested in especially Megamouth shark, realizing it was far more intriguing than I had expected. This led to my in-depth study of various aspects of Megamouth shark, such as distribution, reproduction, and feeding ecology.

Sharkman: How many sharks have you tagged?

Debbie: I’ve been involved in tracking research since I joined the lab, but I couldn’t really tell the real correct number for the total tagged sharks because this is not my main research project. If we want to count the number of sharks (without rays) tagging activity, which I was there (including different types of tags), it could be about 20 sharks, including Whale sharks, Megamouth shark, white-spotted Bamboo shark (Chiloscyllium plagiosum), and Tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier).

Recently, I really appreciated the chance to go on field trips with researchers from the Georgia Aquarium and Mote Marine Laboratory in Savannah and Sarasota. They tagged Bonnethead sharks (Sphyrna tiburo), Lemon sharks (Negaprion brevirostris), Bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas), etc.

Sharkman: Have you retrieved any of the tags back? Can you share some of the info please?

Debbie: As previously mentioned, I have only assisted with the tagging project before. In the past, Hsu et al. (2007) had very interesting Whale shark tagging and release results. Our tagging efforts are still awaiting data accumulation, so I can only share some interesting examples here.

There used to be one over 11-meter Whale shark that was released off northeastern Taiwan and was later sighted in the Philippine waters. In recent years, Dr. Joung has received funding from Glamour Fine Jewelry for a satellite tagging program, and he yielded some results.

One Whale shark tagged in winter migrated from the southwestern waters of Taiwan to Indonesian waters, while another, tagged in summer, migrated south to the Philippine waters. Additionally, another individual moved with the Kuroshio Current to the Miyako and Ishigaki Islands in Japan from winter to spring, remaining in that area for over a month.

On the other hand, since last year, my lab collaborated with the Georgia Aquarium and the Fisheries Research Institute to implement the acoustic telemetry program. Acoustic telemetry is a technique that relies on tagged animals being detected by the deployed receivers. Thus, the animals we tagged since last year are still awaiting detection by receivers (these receivers are typically retrieved every year for battery replacement and data download).

Currently, only our tagged Guitarfish (Rhinobatos spp.) have been detected by our receivers due to their limited activity range. We look forward to seeing more results for other species, including Whale sharks and Megamouth sharks in the future.

Sharkman: From the known reports, Taiwan is the prime location for Megamouths sharks. Do you agree?

Debbie: According to my research, "the prime location" is questionable, because the whole northwestern Pacific seems to be the habitat for Megamouth sharks according to the data reports from different sources. The only difference is that since 2013 and 2020 we have a very complete catch and report system in Taiwan.

Sharkman: In November of 2020 the The authorities issued regulations to protect these sharks. Can you please tell us what these regulations say?

Debbie: The Fisheries Agency, Council of Agriculture (FACOA), has issued a directive prohibiting the capture of Great White sharks (Carcharodon carcharias), Basking sharks (Cetorhinus maximus), and Megamouth sharks. Any incidental catches must be immediately released back into the sea, regardless of the condition of the individual (alive or deceased). However, exceptions may be made for domestic educational or scientific research purposes.

Sharkman: How important is it that all catches are reported?

Debbie: According to the catch and report system, we scientists could gain much information related to the shark and fishery, such as body size, sex, fishing gear, location, target species, etc. Even only with basic catch data, it is possible to gain insights into resource dynamics by calculating catch per unit effort (CPUE) or assessing size-sex trends. For example, in the case of the Megamouth shark, data reported before the fishing ban showed that the average annual catch per vessel was consistently stable, and all captures were from the same fishing method. Due to the very few vessels, operating in areas where Megamouth sharks could be caught, only three vessels remained by the time of the ban, this indirectly suggests that the population of Megamouth sharks was minimally affected by fishing pressure.

ding 3

Sharkman: How and why is it important for the Fishermen and the authorities work together for the conservation of the sharks?

Debbie: Throughout history across different cultures, resources were for utilization, but the concepts of "reasonable" and "sustainable" use is of utmost importance. The primary goal of conservation is to ensure resources sustainability. Regarding marine biological resources, without the cooperation of fishermen in research, we would have no opportunity to understand details such as body size, sex, diet, and reproductive biology, nor could we derive the biological parameters needed for future management strategies.

Sharkman: I am sure that your work has given you quite a few moments that you will never forget. Which is the most memorable one?

Debbie:After joining the lab, the most memorable experience for me was the first field trip to the fish market, the first time I saw an over 3-meter longfin Mako shark (Isurus paucus). I was struck by how huge the animal was.

Sharkman:Is there a Final comment or message that you would like to pass on to our readers?

Debbie: Sustainable fishery resources management needs to proceed with caution, before decision-making, we need many biological parameters, such as body size at maturity, size at birth, growth rate, fecundity, longevity, etc. for population or stock assessment. Collecting this data requires collaboration between scientists, government, and fishermen. By working together, we can promote responsible practices and ensure the sustainable use of marine resources. Sharks, as a crucial component of marine ecosystems, deserve our dedicated efforts for conservation and sustainable management. We protect sharks not only for the health of our oceans but also for future generations to continue studying and appreciating these fascinating creatures. Together, through science, community involvement, and careful decision-making, we can make a difference in safeguarding the future of sharks and the marine environment they inhabit.

Sharkman: True words indeed. Debbie Thank you for being with us here at Sharkman’s World.

Debbie: I am very grateful to you Sharkman for spreading knowledge about different shark species. While science communication is incredibly important, it is equally crucial to convey accurate scientific information. We scientists sometimes may be too serious or boring, but through Sharkman’s World, these topics become much more engaging and interesting!

Sharkman: Thank you again for your kind words.

Debbie with a Megamouth Shark.